Rohmer: A Good Marriage (1982)

Reading about Eric Rohmer over the past few days, I stumbled across an article written by a contemporary of his named Luc Moullet. The article was published in 2012 and effectively acts as a retrospective on Rohmer, his sensibilities and his personality, written by someone with a kind of “inside scoop.” One observation immediately stood out to me:

‘What is fascinating, foremost, in his work is his obstinacy to not go beyond his only or main subject, often summed up, in a somewhat misleading way, by its title: Béatrice Romand wants a good marriage, […] Viewers are reassured. They know where they are going. The what is determined at the start, only the how matters.’

There’s very little contrivance to Rohmer’s films and this is a great part of what makes them so unassuming. For the most part this sense comes from the minimalistic premises he provides himself but there’s also a dual sense of self-consciousness and utmost confidence to how they’re made. Rohmer refuses to promise us anything other than the gossiping and oftentimes banal discussions had by his array of bourgeois twenty-somethings whilst consistently managing to illustrate a near-kaleidoscopic view of their interior, emotional lives. This is to say that oftentimes we know, going into the film, what we’re going to get. The enjoyment and seeming purpose is to witness life, as Rohmer presents it, unfold. As Moullet describes, the how is everything.

The next film I’ll be looking at in my series of essays on Rohmer’s Comedies and Proverbs is Le Beau Mariage or A Good Marriage (or even The Perfect Marriage, French really isn’t my strong suit.) Released in 1982, just a year after the series’ previous instalment, the film’s main and only plotline is concerned with much of the same conflict as The Aviator’s Wife. Sabine, a master’s student splitting her time between Paris where she studies and Le Mans where she works in an antiques store, has grown frustrated with the affair she’s having with Simon, a painter and married man. One night she breaks off the relationship and decides, rather in heat of the moment and seemingly in an act of spite against Simon, that she’s going to get married. Unsure to whom at this point in time, Sabine resolves to be picky and not to settle like she believes Simon to have done himself; ‘Béatrice Romand [Sabine] wants a good marriage.’

Sabine travels home to Le Mans to inform her close friend Clarisse (Arielle Dombasle) of her intentions, much to her friend’s justified amusement. Endeavouring to help her friend and play matchmaker, Clarisse sets Sabine up with her older cousin Edmond (Andre Dussollier) and from here, a tale of awkward interactions and smothered romance sprawls. Sabine chases Edmond as he constantly recedes, seemingly embarrassed and uncomfortable at every turn.

Of great import throughout is each character’s attitude toward marriage and romance, about which we learn most through casual conversations. This is the primary driving force of Moullet’s ‘how’ that we desire from Rohmer’s cinema. The complexity of romance drives and complicates each character’s goals and none more so than our heroine, Sabine.

Sabine herself wants to be a house-wife, already sick of working her part-time job and convinced her degree is leading her nowhere. She also wishes to find the perfect man and both of these goals are frustrated by her own personality. Sabine is relentlessly impatient and ambitious yet she desires a quiet, sedentary life. Her natural inclinations fly in the face of what she claims she wants most. Stated at the outset, Sabine is determined to not settle for an unhappy marriage, not settle for the imperfect man and yet she falls for the first person she meets.

More than this she appears obsessed by the concept of marriage and seems to value it over any kind of meaningful relationship. Talking to her mother (Thamila Mesbah-Detraz), Sabine describes Edmond in terms of his career and his position; knowing nothing of him personally after spending their first date talking about herself. Sabine is little interested in getting to know Edmond because she’s determined that he’s perfect for her already. All there is to do now is convince him that she is too but evidently this doesn’t work for Edmond. He’s not as smitten by her as she is by him. In one moment, Sabine is apparently quite taken by the idea - it never actually happening to her in actuality - of being courted and proclaims plainly that ‘I want [Edmond] to want to marry me,’ and here she gives the game away. This man, who is perfect on paper, is not reciprocating her advances and she can’t accept that because she’s fallen for him already. Later, after they bump into one another, Claude (Vincent Gauthier), Sabine’s ex-lover, asks ‘do you love this guy? It sounds like you want to marry his apartment.’ Sabine is mistaken in her apprehension of facts of the matter due to her own emotional investment and frustrates her own attempts at happiness.

But her mistake is just that, a mistake. Sabine is not some ogress attempting to make Edmond’s life difficult, she may well seem petty and small but she’s also greatly sympathetic. As we learned from our look at The Aviator’s Wife, Rohmer refuses to elevate one party above another and revels in complicating our perceived sympathy or antipathy toward his main players. In key moments, we’re clued into a deep dissatisfaction and discomfort within Sabine. A tragic element to her character that never quite breaches the surface of the text to inform us of how tragic this all really is, but boils beneath it and confuses the romance and humour.

Slowly, it becomes apparent that up to this point, the only relationships Sabine has really engaged in have been various flings and affairs, meddling with married men, disrupting the relationships of others - maybe even for the sole reason that she finds it easy to do so. Sabine’s dissatisfaction seems to arise out of her frustration with her very own impatience. The emotional relationships and companionships she so craves take time and do require the pain of not settling, as she so rightly describes early on, but she but can’t seem to stick with anything for long enough. To her mother, she exclaims ‘I’m sick of being loved for my arse and that’s all!’ Sabine knows what she wants but can never seem to quite attain it and her whole person has somewhat congealed around this fact, around this frustration, this irritation.

Towards the middle of the film, when she bumps into Claude and they catch up for a while, we find Sabine on the backfoot, defending her views on marriage which she sees as wholly reasonable. For perhaps the only time in the film, the main plotline is halted; the scene appears not external to the timeline of story events as it greatly pertains to Sabine’s thoughts at that exact point in time, but it does appear at a time where no character is doing anything to progress or alter the relationship at the centre of everything. Sabine is simply visiting an old friend. Immediately, Sabine’s questioning of Claude’s wife’s career grates, an indication of the kind of relationship she and Claude previously had. She asks Claude whether he thinks his wife would be happier being in the flat, working as a house wife, not being around a class of screaming kids, but with her own. Claude denies this and explains that she’s liberated, able to work - an equal. Claude’s life is the opposite of what Sabine seems to want and the fact that it seems to be working out hurts Sabine. Why couldn’t she have had this with Claude? How is he so happy without her? Why does he not appear to see her as a threat to his marriage anymore? How does she compare to to woman to whom Claude is bound?

But Claude supposes that the breadwinner will always dominate the other, and Sabine sees this as cruel. To Sabine, Claude sees relationships ‘in terms of power,’ whereas she sees them in terms of a ‘pooling of talents.’ There’s a tinge of truth to what Sabine says; it does appear cruel to see everything with regards to power dynamics, denigrating those who choose to stay home because they no longer retain a currency within the relationship, but it’s hard to side with Sabine because of where she seems to be arguing from. Sabine’s responses seem reactionary - justifications for her desire for idleness and not advocacy for the true independence her position implies. At times her reactions are even spiteful, directed at Claude’s jugular, and later retracted when she sees he’s not actually trying to attack her. In this scene, a new light is shed on Sabine, who at first appears so fearsome. Her argumentative, contrarian nature is a defence mechanism, she is protecting herself against impositions from the outside world that she mistakenly sees as threats. And there is yet more tragedy in this, her reaction to the world is so antagonistic, it must be exhausting.

Even Edmond, Sabine’s desire, doesn’t appear spotless, though he may at first. Early on, Edmond just seems to be somewhat caught up in Sabine’s whirlwind of courtship; cringing at every awkward situation, railroaded into silence. But Edmond is clearly not as disinterested as he appears. In each moment that Sabine starts to lose hope, Edmond refuses to pull the trigger and fully walk out. At Sabine’s birthday party, Edmond’s half-advances betray his motivations. He hasn’t called and appears majorly distant, but his actions tell that he’s still somewhat interested. He was thinking about her even though he was keeping her in the dark the entire time. Sabine arguably does tangle him up in some kind of confusing web but after a certain point Edmond makes things significantly worse for the both of them by not communicating anything clearly to her, only to then turn around and use this ambiguity to string her along then subsequently hide his own failings within it.

Sabine is argumentative, insecure and petty, yes. But Edmond is awkward, arguably just as insecure and even somewhat cowardly. They’re not bad people, by any means, but they’re confused and frustrated. And they’re confusing and frustrating to watch. It would be oh so satisfying to see any clear indication of who might be to blame for the dilemma at the heart of everything, but the beauty of the film is that we’re forced to care for real personalities with grating personalities because to a great extent their fundamentally small-scale desires and quiet tragedies are ours.

By the end of the film there’s a suggestion that nothing has changed in Sabine, that she has not learned from her experiences. She finds herself on the train once more, and once more spotting the same man she was taken with in the very first scene. An engineer, or a student like her - what is it that he’s reading? This time, he spots her too and smiles knowingly; as she explains herself, she finds it easy to pick guys up - but that’s not what she wants. Is this just another of those guys? Has nothing changed? The circularity of the film, the fact that Sabine is in almost exactly the same situation from the very start of the film, suggests not. But who knows? Maybe there’s more of a hopefulness here than I’m able to see.

Comparatively, there appears far less irony in Rohmer’s framing of The Good Marriage’s narrative than in that of its predecessor, The Aviator’s Wife. Where in the former there’s a sense of humour in the way the film is structured - the way that key information is hidden in order to produce a kind of tragicomic revelation - in the latter the irony is present only within the characters themselves - in that they constantly work against themselves - and works far more subtly. Irony in general, though, seems to be key to understanding Rohmer as not just an artist but in his own world view and it seems worthwhile drilling into the subject at least a bit.

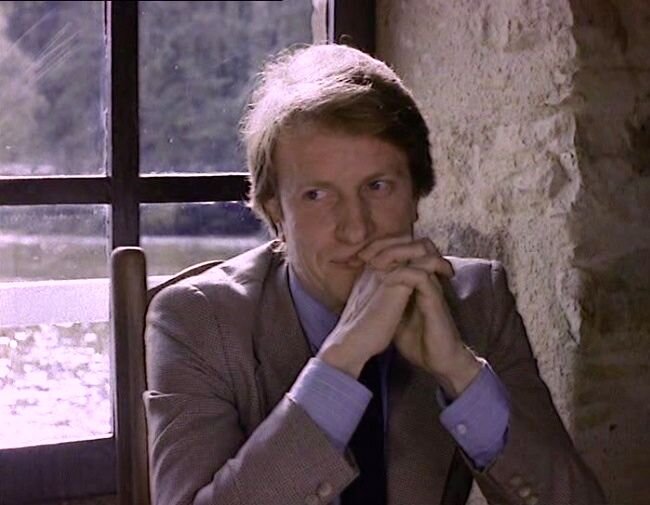

In his own piece, Gilbert Adair - the novelist and film critic - creates another profile of the critic-turned-filmmaker. Adair illustrates Rohmer as someone rather amused and humoured by the world around him.

‘When I once interviewed him for Sight and Sound magazine, he remarked, as though it went without saying, that all his films were comedies, whatever the apparent subject – just as life itself, he argued, was a comedy disguised as a tragedy.’

There appears an urge on seeing this worldview to see Rohmer as somewhat cold. Taking personal delight in the tragedies of others and of his characters, but Adair refutes this too.

Yet he never despised his characters […] In film after film, their plots halfway between Marivaux and an episode of Friends, he meticulously unravelled the moral deceptions and emotional imbroglios in which his brainy dandies and scheming nymphets infallibly entangle themselves, without ever withdrawing his sympathy for, or indeed his love of, them.

And I must agree. There is indeed a sense of irony in his films, but Rohmer never takes this to extent of ironic detachment. From start to finish, we’re deeply involved in the interior worlds of these groups of ‘brainy dandies and scheming nymphets,’ so much so that they never once become the targets of the humour. Much as we might scoff at a remark of Sabine’s, we’re forced to watch her unravel her tangled logic and gradually we can at the very least start to see what she’s coming from, even though she never really solves her problems. There comes an image, not of Rohmer sitting at his writer’s desk humouring himself with the vapidity of his characters, but of him sitting at one of the various cafes he’s depicted, looking back with them and laughing at their poor luck. At the risk of stealing far too much from the late Gilbert Adair’s article (it’s a really interesting read) he does conclude his profile in a brilliant way and it illustrates my point perfectly:

‘I recently encountered a word I didn't know, along with its definition. The word was sprezzatura and the definition was that of the 16th-century Italian diplomat, courtier and writer Baldassare Castiglione. Wikipedia offers two definitions, the first of which seems to me ideally applicable to Rohmer himself, and the second to his dramatis personae. The first is: "A certain nonchalance, so as to conceal all art and make whatever one does or says appear to be without effort and almost without thought." The second is: "A form of defensive irony: the ability to disguise what one really desires, feels, thinks, and means or intends behind a mask of apparent reticence and nonchalance." I couldn't have put it better myself.’

Well neither could I. Rohmer’s use of irony is just as human and nuanced as Sabine’s argumentative flair and it imbues his films with a heightened sense of realism. The very title of the series of films currently under examination - Comedies and Proverbs - echoes this sensibility of his. Rohmer seems to dismiss his own works as simple exercises in humour and generality but there’s certainly more to be found within than Rohmer wants to let on - might we then say that this is simply nonchalance or a defensive irony? Is there a humour to be found in Sabine’s struggles against her own impulsivity or is Rohmer simply asking us not to take it too seriously? Maybe I’ve missed the point in writing about it.